By Natalie David and Vanessa Pham

Lock your doors… hide your kids… the ferocious assassin (bug) is here in the Lehigh Valley.

Not so fast! The wheel bug (Arilus cristatus), a member of the large assassin bug family (Reduviidae), is both a fierce predator yet a beneficial horticultural insect.

The wheel bug earned its name from one of its physical features: a semicircular crest that sits on its thorax that looks more like a chicken’s comb than a wheel! No other insect in the United States possesses this unique structure! Scientists are not sure why the wheel bug has this interesting structure, but it may be a way for individuals to recognize each other or help make them more undesirable for predators to eat.

“Arilus cristatus, Wheel bug #4″ by David Illig is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

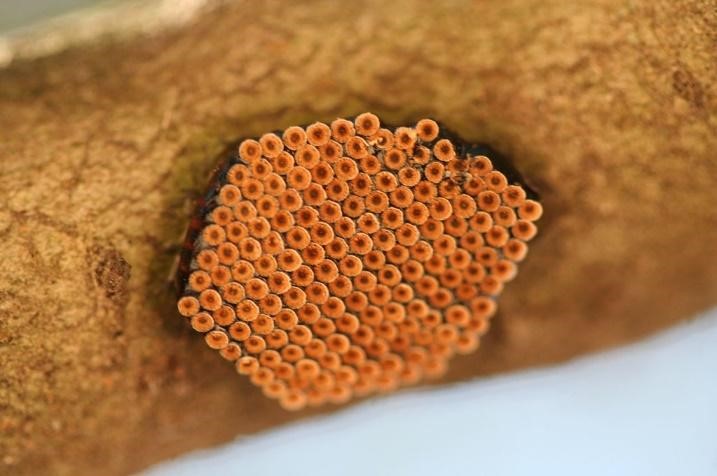

Like other true bugs, the wheel bug has an incomplete metamorphosis, with five larval instar stages of development until the nymph molts into its adult form. Wheel bugs have one generation per year and overwinters during the egg stage. The pictures below highlight these different stages! After mating occurs in the fall, the mother lays her eggs in a secure and protective gummy case on tree trunks and larger branches. Once spring arrives, the eggs hatch into their “adolescent” nymph form but are too young to have their wheel structure yet! Three months and many molts later, they mature into adults. You can find these insects in favored habitats of goldenrods, sunflowers, and various fruit trees ranging across nearly the entire continental United States as well as Mexico and Guatemala.

Pay attention to its long, sucking mouthpart!

With permission from Melinda Fawver

These bugs leave a painful bite that can last many hours. The pain and burning sensations are due to the injection of saliva from large glands, which is typically meant to digest soft-bodied insect prey. The vast majority of bites are not a major reason for concern as the reaction is typically localized. Doctors recommend an Epsom Salt soak to help with the healing process and reduce pain, as well as antibacterial ointments found at your local pharmacy to prevent infection.

Dr. Richard Neisenbaum, the director of Sustainability Studies at Muhlenberg College, recounted one memorable encounter with a wheel bug. He reminisces: “One time I was at Muhlenberg’s Graver Arboretum with botany students. I often find insects and throw them into the pond so the students can watch the fish come up and feed. I unwittingly grabbed a wheel bug for this demonstration, and it bit me on the palm of my hand. The students got to witness my reaction: #@%$! The demonstration ended as the insect landed on the surface of the pond, and a smallmouth bass rose from the depths to consume it. I guess I got what I deserved….”

The saliva of wheel bugs contains potent hemolytic-neurotoxin venom that paralyzes their prey. Maybe there’s a relation to Marvel Comics Venom? These bugs are known as generalist predators, meaning they can consume a wide range of prey. Some prey of choice for wheel bug adults are caterpillars, beetles, and wasps. Additionally, wheel bugs feed on leaf miner larvae by piercing the animal in its burrow inside the leaf. These larvae attack vegetable crops and ornamental plants. Wheel bug nymphs love to slurp the innards of aphids and other small insects. Zooop!

As a top predator for insects, the wheel bug plays a vital role in the ecosystem by controlling the number of insect pests. It is also one of the few predators that attack the brown marmorated stink bug, a serious invasive pest of many crop plants and a household pest. Introduced to the Lehigh Valley in 2015, the spotted lanternfly is another invasive pest to forestry and agriculture– especially grapevines, hops, and other fruit crops and woody trees. Wheel bugs have been observed feeding on spotted lanternflies in the Lehigh Valley on many occasions over the last six years. It sounds like wheel bugs may be a secret “hero.” Although wheel bugs are most active during the day; also, they are often attracted to lights in the evenings, undoubtedly in search of other insects that are also attracted by the lights.

Pennsylvania, USA

With permission from James Occi

Besides their notable bite, wheel bugs protect themselves from predators through camouflaging with their environment and a… stink bomb? That’s right! When threatened, these bugs extrude secretions from Brindley’s gland. The secretions are a toxic blend that produces a pungent smell that is not as strong as a stink bug’s secretions but is still very noticeable. Guess you have to look out for that!

Initially, entomologists believed that these stink bombs were released from two bright-red subrectal glands. However, researchers recently noticed that these sacs were only found on females and released a pleasant scent, potentially indicating a function involved with mating. However, wheel bug females are both attractive and deadly. A blessing and a curse. After copulation, wheel bug females have been seen killing and feeding upon their male mate.

Even though these insects are considered solitary, they still can communicate through “chirping” sounds by rubbing the tip of the snout back and forth on the grooves between their front legs. However, more information on this function is still needed! These bugs fly slowly, and they make a noisy buzzing sound as they fly.

Many people look at the wheel bug and confuse it with the kissing bug. However, unlike the wheel bug, the kissing bug is markedly different and is not found in the Lehigh Valley region. Kissing bugs are active during the night and suck blood versus insect fluids. They do not have the distinctive cog-shaped appendage on their thorax. Also, wheel bugs are much larger, measuring over 1.25 inches long (which is around the size of a water bottle cap), while kissing bugs are the size of a penny. Even with this in mind, the kissing bug that is villainized for transmitting Chagas disease is a poor vector of disease. This is because you don’t get Chagas disease from a bite; the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi (a single-celled parasite) is only transferred to you if the insect defecates in an open wound. The figure below has a side-by-side comparison of these two Reduviidae bugs.

Next time you are taking a hike in the Lehigh Valley, remember to respect the wheel bugs and let them roll, roll, roll along! Happy bug spotting!